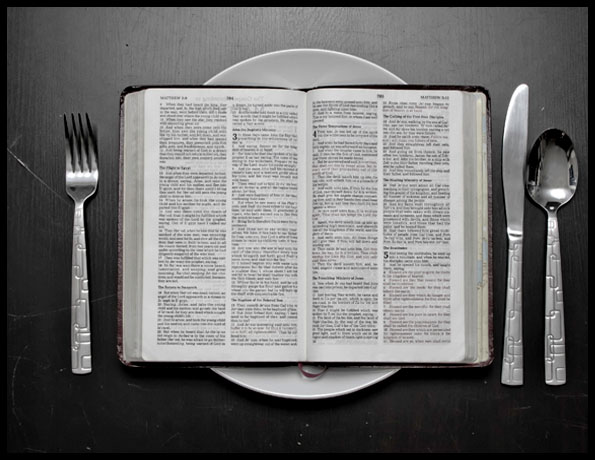

Fasting the Right Way

Matthew 6:16-18

It is amazing how easy we are deceived when it comes to religious matters. So many things that start off as incentives to repentance and godliness develop into vicious idols.

What starts as an aid to holiness ends up as the triple trap of legalism, self-righteousness, and superstition.

That is what happened with the bronze snake in the wilderness. Although it was ordered and used by God (Num. 21:4–9), it became such a religious nonsense in later times that Hezekiah destroyed it (2 Kings 18:4).

The same thing happens with other forms of religious observance or spiritual discipline. One may with fine purpose and good reason start “journaling” as a discipline that breeds honesty and self-examination.

Soon, it can easily slide into the triple trap: in your mind you so establish journaling as the clearest evidence of personal growth and loyalty to Christ that you look down your nose at those who do not commit themselves to the same discipline.

Then, you pat yourself on the back every day that you maintain the practice, which has become (legalism); you begin to think that only the most mature saints keep spiritual journals, you qualify, but you think about so many who do not (self-righteousness);

You begin to think that there is something in the act itself, or in the paper, or in the writing, that is a necessary means of grace, a special channel of divine pleasure or truth, which is in reality, (superstition). When that happens, it is the time to throw away your journal.

Just as easy, fasting can become a similar sort of trap.

The Old Testament Fast Prescribed

The Day of Atonement

Leviticus 16;29 And it shall be a statute for ever unto you: in the seventh month, on the tenth day of the month, ye shall afflict your souls, and shall do no manner of work, the home-born, or the stranger that sojourneth among you: 30for on this day shall atonement be made for you, to cleanse you; from all your sins shall ye be clean before Jehovah. 31It is a sabbath of solemn rest unto you, and ye shall afflict your souls; it is a statute for ever.

In addition to the fast on the Day of Atonement, the Old Testament mentions general and individual fasts undertaken for a variety of purposes, including mourning, repentance, and seeking divine deliverance. Fasting was a means of asking God to have pity and relent from inflicting punishment on the person or people praying.

The first five verses of Isaiah 58 expose and condemn the wrong kind of fast, while verses 6–12 describe the kind of fast that pleases God. The first is bound up with hypocrisy. People maintain their fasts, but quarrel in the family (58:4). Their fasts do not stop them from exploiting their workers (58:3b). These religious people are getting restless: “We tried fasting,” they say, “and it didn’t work” (58:3).

At a superficial level they seem to have a hunger for God and his way (58:2). The truth is that they are beginning to treat the fast as if it were a bit of magic: because I’ve kept the fast, God has to bless me. Such thinking is both terribly sad and terribly evil.

By contrast, the fast that pleases God is marked by genuine repentance (58:6–12). Not only does it turn away from self-indulgence but it actively shares with the poor (58:7), and intentionally strives “to loose the chains of injustice,” “to set the oppressed free and break every yoke” (58:7), to abjure “malicious talk” (58:9). This is the fast that brings God’s blessing (58:8–12).

In general, fasting in the OT was abused. Instead of a sincere act of self-renunciation and submission to God, fasting became externalized as an empty ritual in which a pretense of piety was presented as a public image. Hence, the prophets cry out against the callousness of such hypocrisy. Jeremiah records Yahweh as saying, “Though they fast, I will not hear their cry” (14:12; see Is 58:1–10.).

Zechariah deals with this issue, it is triggered by a question. The question is posed by a delegation from the exiles about liturgical observance. The Jews in Babylon wanted to remain in liturgical sync with the Jerusalemites. Their delegation is pretty early in the life of the returned community—late 518 B.C., just over twenty years since the initial restoration and only a year since the commitment to rebuild the temple, under the preaching of Haggai, had taken hold.

The formal answer to their question is not given until 8:18–19. Yet the focus on fasting as a ritual to be observed calls forth a word from the Lord through the prophet. They press beyond merely formal observance and call the people, yet again, to fundamental issues. Zechariah 7:5–14 provide the first barrage of the prophetic response.

7 And it came to pass in the fourth year of king Darius, that the word of Jehovah came unto Zechariah in the fourth day of the ninth month, even in Chislev. 2Now they of Beth-el had sent Sharezer and Regem-melech, and their men, to entreat the favor of Jehovah, 3and to speak unto the priests of the house of Jehovah of hosts, and to the prophets, saying, Should I weep in the fifth month, separating myself, as I have done these so many years? 4Then came the word of Jehovah of hosts unto me, saying, 5Speak unto all the people of the land, and to the priests, saying, When ye fasted and mourned in the fifth and in the seventh month, even these seventy years, did ye at all fast unto me, even to me?

6And when ye eat, and when ye drink, do not ye eat for yourselves, and drink for yourselves? 7Should ye not hear the words which Jehovah cried by the former prophets, when Jerusalem was inhabited and in prosperity, and the cities thereof round about her, and the South and the lowland were inhabited?

Is our religion for us or for God?

The prophet Zechariah faithfully conveys God’s question to the delegates of the exiles: when across seventy years (i.e., from 587) they faithfully fasted on certain days, thinking those were the “proper” days, did they do so primarily as an act of devotion to God, or out of some self-centered motivation of wanting to feel good about themselves (7:5–7)?

How much of the religious practice was offered to God?

Does our religion elevate ritual above morality?

That is the burden of Zechariah’s stinging review of earlier Jewish history (7:8–12). Zechariah is Implicitly asking, is their concern for liturgical uniformity matched by a passionate commitment to “show mercy and compassion to one another,” and to abominate the oppression of the weak and helpless in society (7:9–10).

Does our religion prompt us passionately to follow God’s words, or to pursue our own religious agendas?

“When I called, they did not listen; so when they called, I would not listen” (7:13), the Lord Almighty announces. Passionate intensity about the details of religion, including liturgical reformation, is worse than useless if it is not accompanied by a holy life. In true religion, nothing, nothing at all, is more important than whole-hearted and unqualified obedience to the words of God.

11 The LORD said to me: “Do not pray for the welfare of this people. 12 Though they fast, I will not hear their cry, and though they offer burnt offering and grain offering, I will not accept them. But I will consume them by the sword, by famine, and by pestilence.” Jeremiah 14

The setting for the NT understanding of fasting lies in the development of the rabbinic tradition that grew out of the period between the Testaments, during which fasting became the distinguishing mark of the pious Jew, even though it was largely still ritualistic. Vows were confirmed by fasting, remorse and penitence were accompanied by fasting, and prayer was supported by fasting (1 Macc 3:47). Special fast days were observed, some voluntarily imposed (2 Macc 13:12;).

This developed into a rabbinic tradition in which fasting was viewed for merit, and therefore became the primary act of demonstrating piety. It was, however, a false piety consisting mostly in the externals of fastidious observance of fast days, both public and private.

With the exception of ascetic groups such as the disciples of John the Baptist, the prevailing mood of fasting when Jesus appeared on the scene was one of mournful sadness, an obligatory necessity, a self-imposed requirement to produce the discipline of self-denial.

Jesus’ understanding of fasting is significant in that it represents a shift in the role of fasting. His initial attitude undoubtedly reflected the fact that he grew up participating in the regular fasts and therefore shared the prevailing teachings of his day.

But, his mature teaching about fasting broke with the rabbinic tradition.

The three most common acts or piety among many Jews were, prayer, fasting, and alms, giving money to the poor. So when Jesus’ disciples seemed a little indifferent to the second, it was bound to provoke interest. The Pharisees fasted; the disciples of John the Baptist fasted. But fasting was not characteristic of Jesus’ disciples. Why not? (Mark 2:18–22.)

Jesus defends this behavior using a parable of a bridegroom. He indicates that His presence, like a bridegroom’s, was a cause for celebration, making fasting inappropriate. According to Jesus, a time for mourning (and fasting) would be fitting when the bridegroom is taken away (Matt 9:15; Mark 2:20; Luke 5:34).

Jesus’ response is stunning: “How can the guests of the bridegroom fast while he is with them?

They cannot, so long as they have him with them. But the time will come when the bridegroom will be taken from them, and on that day they will fast” (2:19–20).

Jesus is profoundly self-aware, deeply conscious that he himself is the messianic bridegroom, and that in his immediate presence the proper response is joy. The kingdom was dawning; the king was already present; the day of promised blessings was breaking out. This was not a time for mourning, signaled by fasting.

Yet when Jesus went on to speak of the bridegroom being taken away from his disciples, and that this event would provoke mourning, it is very doubtful if anyone, at the time, grasped the significance of His words. After all, when the Messiah came, there would be righteousness and the triumph of God. Who could speak of the Messiah being taken away? The entire analogy of the bridegroom was becoming hard to grasp.

Right now, sorrow and fasting were frankly incongruous. The promised Messiah, the heavenly Bridegroom, was among them.

Jesus point was, with the dawning of the kingdom, the traditional structures of life and forms of piety would change. It would be inappropriate to graft the new onto the old, as if the old were the supporting structure—in precisely the same way that it is inappropriate to repair a large rent in an old garment by using new, unshrunk cloth, or use old and brittle wineskins to contain new wine still fermenting, whose gases will doubtless explode the old skin.

The old does not support the new; it points to it, prepares for it, and then gives way to it. Jesus is preparing his disciples for the massive changes that were dawning.

On a day when the sins of the people were to be atoned for, afflicting or denying oneself by fasting would serve as an outward sign of inner repentance for breaking God’s law.

Another purpose of this fast may have been the belief that the temporary suspension of normal activities such as eating allowed one to focus on God and acknowledge dependence on Him

Jesus and Fasting

Matthew 6:16–18

16Moreover when ye fast, be not, as the hypocrites, of a sad countenance: for they disfigure their faces, that they may be seen of men to fast. Verily I say unto you, They have received their reward. 17But thou, when thou fastest, anoint thy head, and wash thy face; 18that thou be not seen of men to fast, but of thy Father who is in secret: and thy Father, who seeth in secret, shall recompense thee.

In the Sermon on the Mount (Matt 6:16–18), Jesus criticizes those who fast hypocritically in order to attract attention. He tells people to give alms, pray, and fast in ways that are visible only to God. They should not mar their faces or look gloomy; instead, they should wash their faces and put oil on their heads so that only God knows they are fasting.

The trouble is that the human heart is exhaustively deceitful, and virtually anything you do before the Lord can be twisted this way to make a sign, a piece of showmanship. God help us.

“When you fast, put oil on your head and wash your face …” Oil is a sign of joy. The idea is simply go on out and do what’s normal. Spray on your deodorant or use whatever, but do what’s normal. Don’t do something special. If you usually spray on your deodorant, then spray on your deodorant when you’re fasting too. Don’t do anything different. Don’t show that you’re fasting.

The point is not to change our daily behavior during any voluntary act of piety. The Father alone knows.

Who are trying to please?

That’s the whole question. For all the negatives that are given in this chapter, there is the converse positive. Real piety, real godliness, real holiness is clean, attractive, and wonderful. The real beauty of righteousness must not be tarnished by sham.

God help us.